Charles E. Hill

October 18, 2010

The Huffington Post

Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. These are the Bible's familiar four Gospels, received as Holy Scripture by all major branches of Christianity. From ancient times to the present, these four books have been the gateway to Jesus and his teaching. Friends and foes alike have formed their ideas about Jesus mainly from these books. But why these? Weren't there once other Gospels which for some reason were excluded? How is it that just these four made it into the Bible, and who was it that chose them? If members of the general public have been paying attention, they may know the story by heart, for it has been told in recent best-selling books, novels, and in theaters. Recently, I heard it from a man on a plane and my son heard it in a university classroom. Here is the basic story line.

Gospels about Jesus once flourished. As one scholar has recently put it, they were "breeding like rabbits." Each of the varied Christian sects pushed its own version(s) and competition was lively. This "free market" for Jesus literature meant that, for many years and in many places, some now-forgotten Gospels were at least as popular as the ones that now headline the Christian New Testament. Gradually, however, one of the competing sects was able to gain the upper hand over its rivals. And when it finally declared victory in the fourth century, fully 300 years after Jesus walked the earth, it decreed that its four Gospels were, and had always been, the standard for the church Jesus founded. The "winners," supported by the powerful emperor Constantine the Great, then got to write the histories -- and make the Bibles.

As familiar as the narrative has become, however, it has serious flaws. I wrote Who Chose the Gospels? (Oxford, 2010) for any in the general public who might be interested in a readable account of the scholarship behind this popular story line and in a critique of that scholarship. If the story line has many of the qualities of a gripping conspiracy theory, it is because it basically is a conspiracy theory. And like most conspiracy theories, it tends to be long on drama and somewhat short on reality.

There once were, of course, other Gospels. The public got to see one up close in the spring of 2006 when the recently recovered gnostic Gospel of Judas was unveiled in front of rolling cameras. A cadre of scholars was on hand to deliver the now less-than-startling news that "Christianity was once diverse." For a good many years, some academics have been stumping for another text that somehow slipped through the church fathers' fingers: the Gospel of Thomas. Some would like to make it the long lost conversation partner of the author of the Gospel of John. Not to be forgotten is the venerable "Q" (short for the German Quelle, meaning "source"), the hypothetical inventory of Jesus' sayings which many believe was used by both Matthew and Luke when they wrote their Gospels. Standing up for certain new-old Gospels has taken on an ideological importance, much like the cause of civil rights. Why should fighting discrimination end with people and not with books?

Yet before there were the many Gospels, there were only the four. Not that the four were necessarily the very first writings about Jesus ever scribed, but they are the earliest which we now have. And they are the earliest whose existence we are actually sure of. Yes, the Gospel writers may have used sources, like Q. They may have written earlier editions ("Proto-Matthew," "Proto-Luke," and the like, as they are named). Possibly there were even other Gospels from the first century which we don't know about. But if such things ever existed, we have no good evidence that they ever circulated, or were intended to circulate, among groups of churches as authoritative accounts of the life of Jesus.

That scholars spend good portions of their careers writing about these alternative Gospels and reconstructing Gospel sources that no one has ever reported seeing, though, is a good thing. Such efforts help us imagine how the Gospels were composed, and they give us valuable insights into all early forms of Christianity, both "winners" and "losers".

There is something attractive about the idea of a primordial, Edenic age of natural diversity, from which the church fell into the original sin of greater ecclesiastical unity. But then why do the remains of history seem to indicate that, even amid considerable second-century diversity, there was a mainstream of Christian thought which held a stable, core set of theological beliefs (e.g., that God really did make the world and that Jesus really was both divine and human), as well as a core set of ethical norms? And why does it appear that this Christian mainstream had more in common with the apostle Paul (they preserved his letters) and with the original disciples of Jesus than these other sects did? Here is where the conspiracy theory comes in. This imbalance in the surviving data is explained by the winners' successful campaign to destroy as much of the counter evidence as they could. (Never mind that time and the elements would have destroyed most of them anyway, as they have destroyed most of what the winners tried to preserve.)

Here I will mention one claimed proof for this conspiracy theory, and one stubborn problem it faces.

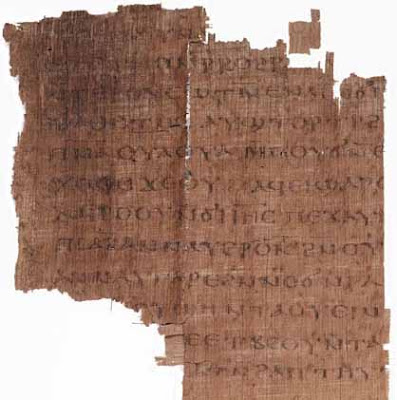

Proof is said to reside in the ancient papyrus documents which archaeologists have dug from the sands of Egypt over the past century and a quarter. The Christian books yielded up by the unbiased, ancient trash heaps are, we are told, mostly books which were excluded from the New Testament. This would seem to show that the four Gospels were once minority reports and that some popular alternatives have been suppressed by the "winners." All I will say here is that the papyri have both less and more to tell us than this argument lets on.

The problem for the conspiracy theory is a man named Irenaeus. Irenaeus was crystal clear in his claim that the church, from the time of the apostles, had received just four authoritative Gospels -- Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John -- and that all the others were bogus. This is just what we would expect from a fourth-century re-writer of history. The problem is that Irenaeus wrote in the second century, long before the conspiratorial rewriting of history is supposed to have taken place.

Does, then, the conspiracy approach to early Christian history, in either its popular or its academic forms, have it right? Should it bother anyone that those who stress so loudly that the winners wrote the histories are the ones now writing the histories? Let the reader judge ... but also be aware of conspiracies.